The UCSB Library, Special Collection Archive, houses all of the Santa Cruz Island NRS historical records. The records have been added to the California State OAC (On-Line Archive of California) system. You can find the research catalog to these records at this link.

The log of Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo contains the first-known written account of Santa Cruz Island. Cabrillo entered the Santa Barbara Channel in 1542, fifty years after the landing of Columbus.

More than two hundred years passed before Juan Pérez, leading the sea component of Gaspar de Portolá’s California expeditions, claimed SCI for the King of Spain in 1769. Historians credit the Pérez party with naming the island Santa Cruz, or Holy Cross,” after a group of Chumash returned a walking staff ornamented with an iron cross that a Catholic priest had lost onshore. By the early 1800s, the island’s native population had been devastated by measles and other introduced epidemics; the last survivors were taken to mainland missions by 1814. Eight years later, Spanish rule in California gave way to Mexican rule. Andre Castillero became the first private owner of Santa Cruz Island in 1839 when he received it as a Mexican land grant, the validity of which was upheld 25 years later in a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision. According to the terms of the grant, the island’s boundary extends to the constantly shifting water’s edge; the other Channel Islands, along with the rest of coastal California, are owned to the mean high-tide line.

Historical records show that by 1853, a large herd of sheep, along with pigs and horses, resided on SCI. Some of the buildings from the early 1860s still stand, including one at Christy Ranch. Ten San Francisco businessmen purchased the island in 1869, forming the Santa Cruz Island Company. By 1880, the company’s major stockholder, Justinian Caire, had become its sole owner. Over the next four decades, a small, self-contained community blossomed in the central valley, eventually including several ranch buildings, a blacksmith shop, a chapel, and a winery.

To pollinate the vineyards and produce honey, Caire kept European bees, which were reportedly on the island when he arrived. Also introduced by the mid 1880's was a variety of exotic vegetation that has since naturalized, including fennel and Italian stone pine; some of California’s oldest and tallest eucalyptus trees grow in a large grove near the reserve field station. Wool and wine production, however, remained the principal venture of the Santa Cruz Island Company. Extensively vineyards grew in the central valley, and thousands of sheep ranged throughout the island.

Caire also constructed ranch facilities at Prisoners’ Harbor, the island’s principal port, as well as eight outposts scattered along the central valley and at each end. Many of these wooden and adobe structures are still being used and remain a valuable historic resource.

After Caire’s death, a long court battle over island management ensued among his heirs, and in 1925 the courts partitioned SCI. The eastern tenth, later known as the Gherini property, remained with Caire’s descendants until the early 1990s, when the National Park Service began acquiring it for the Channel Islands National Park. The western portion was purchased in 1937 by Edwin L. Stanton, a Los Angeles businessman. Stanton attempted to revive the sheep business by mixing domesticated sheep with the then-feral population, but this operation soon became unmanageable on the island’s rugged terrain. Many sheep were sent to market, and the company switched to cattle.

For the next half a century on SCI, the Stanton family operated a nineteenth-century-style rancho. In 1957, Edwin’s son, Dr. Carey Stanton, left his mainland medical practice and moved to the island. For many years he was its only registered voter. Like his father, Dr. Stanton recognized the importance of documenting the island’s natural and human history; the Stantons’ detailed records and collections now reside with the Santa Cruz Island Foundation in Carpinteria, CA. Information and historical accounts can be found at Islapedia, on-line, authored by Santa Cruz Island President and Historian, Marla Daily.

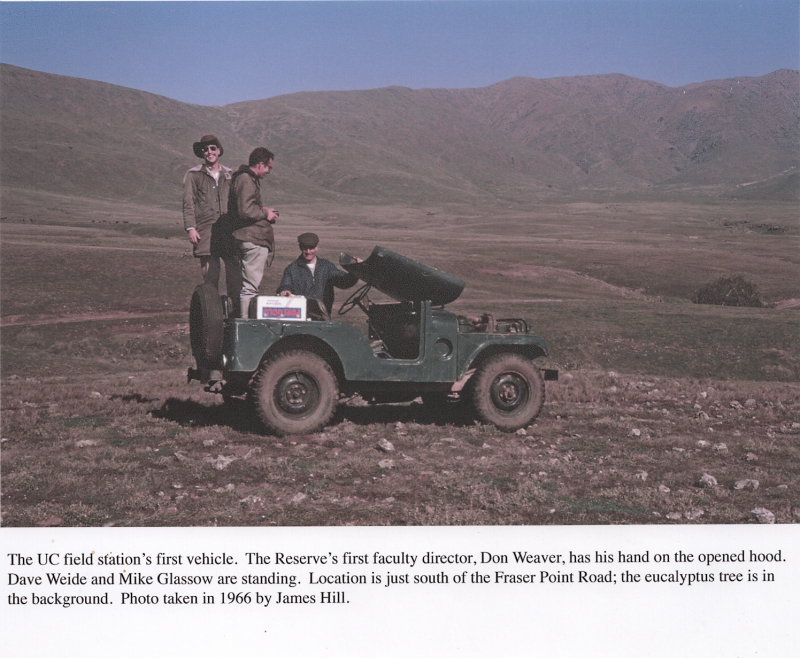

In his quest for information regarding SCI, Dr. Stanton welcomed scientists. His relationship with the University of California began in 1964, when UC Santa Barbara held is summer field geology class on the island for the first time.

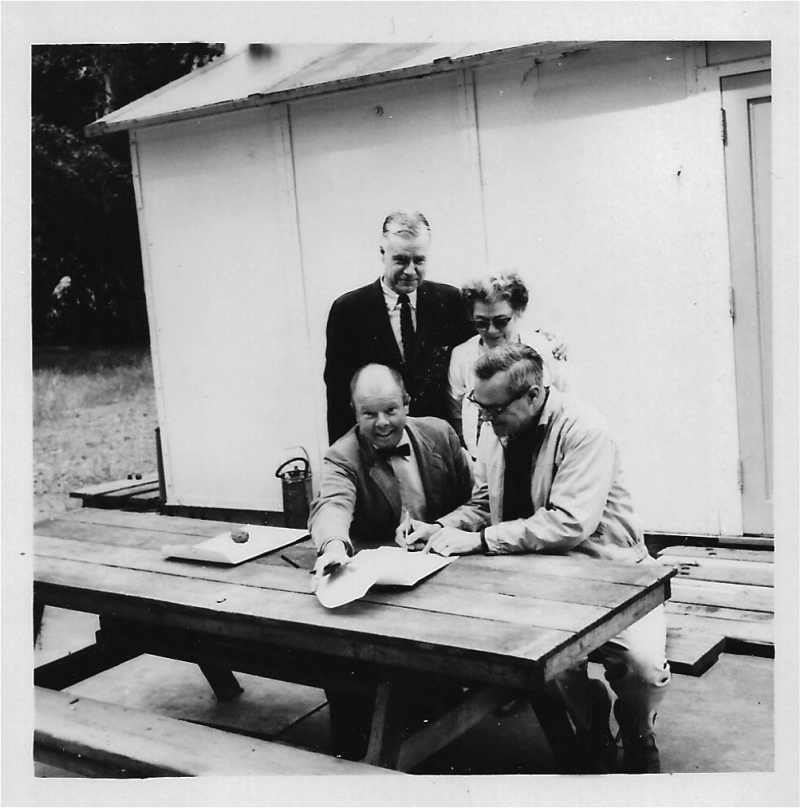

The venture was so successful that the University entered into a formal agreement with Dr. Stanton and the Santa Cruz Island Company in 1966 to establish a field station to support teaching and research. In 1973, this facility, along with the rest of the company’s 22,064 hectares (54,520 acres), became part of UC’s Natural Reserve System (NRS).

In 1973, this facility, along with the rest of the company's 22,064 hectors (55,520 acres) became part of UC's Natural Reserve System (NRS)

To protect the island’s future as well as to preserve its past, Dr. Stanton initiated the sale of the company’s holdings to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in 1978 for a fraction of their market value. TNC moved swiftly to remove feral sheep from the reserve. When Dr. Stanton died in December 1987, the remaining land and assets of the Santa Cruz Island Company transferred to TNC, and the era of private family ownership of SCI came to an end.

The NRS continues to provide facilities and access to the island for instruction and research through a license agreement with The Nature Conservancy. Together TNC and the SCIR have also begun to develop strategies and implement programs designed to remove non-native invasive species, restore damaged habitats, and improve the overall understanding of the island’s natural systems.

Click here to watch a YouTube video of an NPS presentation on The Channel Islands Biological Survey from 1939-1941.